By Patrick Bray

DLIFLC Public Affairs

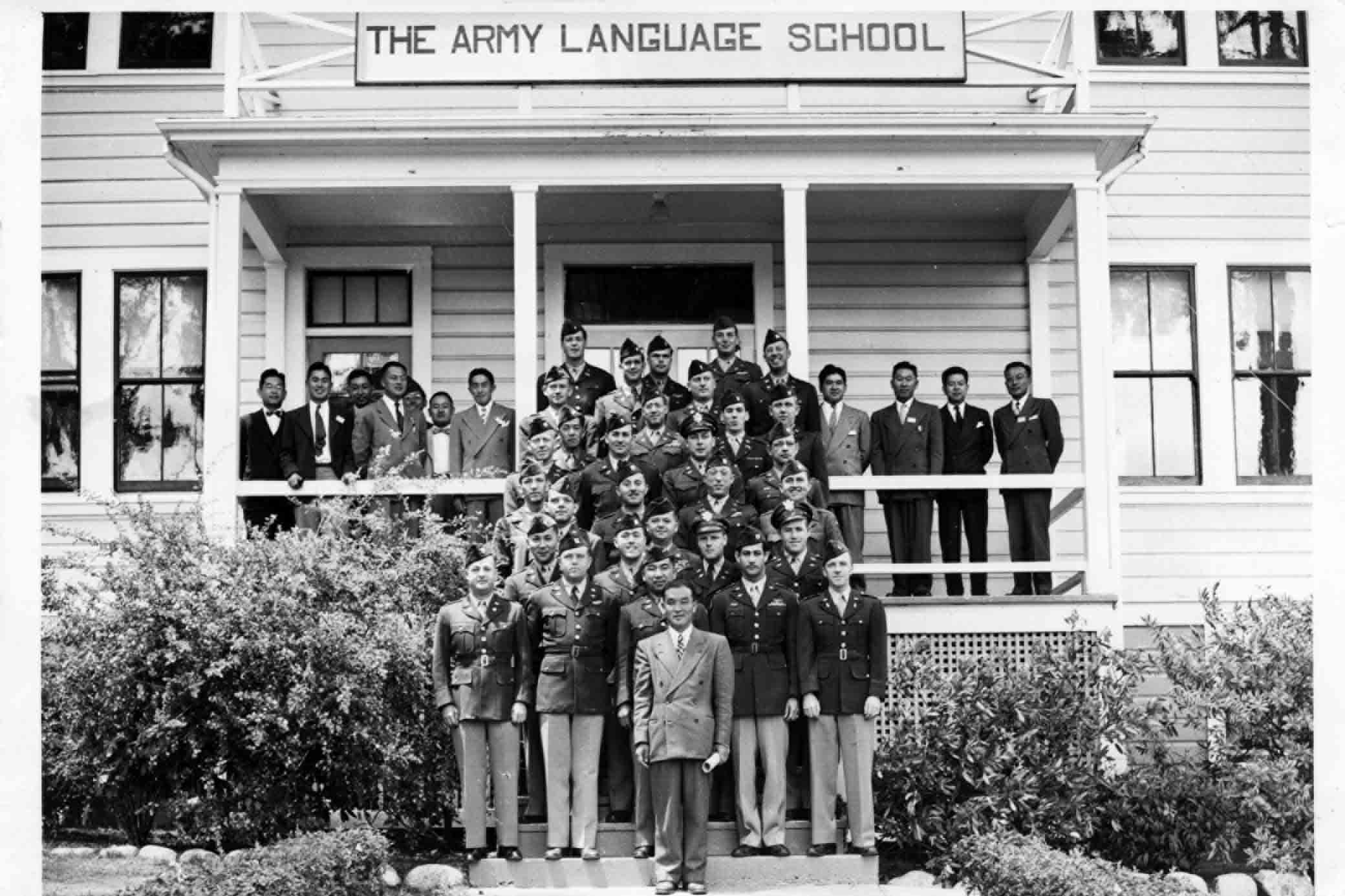

MONTEREY, Calif. – In 1946 the Military Intelligence Service Language School moved from Fort Snelling, Minnesota, to the Presidio of Monterey, California. The school almost went to Japan, but was declined by Gen. Douglas MacArthur who did not have the facilities and recognized that service members would not serve full tours due to the postwar drawdown.

The Presidio of Monterey was the better option as it previously served as the Civil Affairs staging area for troops deploying to the Far East as part of the occupation forces. Although Japanese was the main focus in language training at first, the single-language MISLS became the multi-language Army Language School. The Army added several languages in the years following World War II.

Shortly after the relocation, the military started recruiting native speakers of European and Asian languages. Each language department’s history is unique and these languages were added, to some effect, as a result of the rapidly changing military needs of a postwar world.

Col. Elliott Thorpe, the school’s commandant, recognized the need for understanding the Russian-speaking world. In September 1946 the school hired a graduate student from Stanford University, Gleb Drujina, to join two other instructors to form a Russian class. Their first class began with eight students in January 1947. The looming threat of the Soviet Union and communism would see Russian grow vastly into the largest program during the Cold War.

The Military Intelligence Service Language School became the Army Language School when it moved from Minnesota to the Presidio of Monterey, California, in 1946. Although Japanese was the main focus in language training at first, the Army added several languages in the years following World War II. (U.S. Army photo)

The Truman Doctrine of March 1947 stated that the U.S. should give support to countries or peoples threatened by communism. This would keep the U.S. vested in Europe and the Far East to include aid against the Chinese communist threat. Chinese and Korean, cancelled after being found unproductive in 1945 while still in Minnesota, were reinstated out of necessity. The size of the Chinese Mandarin Department has risen and fallen like so many of the departments. Predictably following the world situation, the department grew to record size during the Korean War only to be reduced to a much smaller size after peace was established on the Korean peninsula. The hostilities in Vietnam and China’s role as a North Vietnam ally lead to another rise in student population and faculty strength in the 1960s.

American interest in the Middle East was also growing and with that came the need for Arabic speakers. Kamil Said moved to the Monterey area in September 1947, at the request of a friend, to lay the groundwork for the first Arabic program at the Army Language School. Originally from Iraq, he came to the U.S. twice to study and stayed on at the language school in Monterey.

In 1947, Persian, Albanian, Greek and Turkish were added and organized in the same section at the school. The Persian program was put together in haste, due to geopolitical reasons and the U.S. interest in the Middle East, especially in Iran. The Persian department started with only four instructors and no textbooks or other instructional aids. Instructors relied solely on their own creativity to provide the necessary material needed for students. All materials were handwritten while tests were administered every other week.

A communist backed insurgency prompted the U.S. to offer aid to Greece during the 1947-1949 Greek Civil War, thus beginning the Greek program.

The Military Intelligence Service Language School became the Army Language School when it moved from Minnesota to the Presidio of Monterey, California, in 1946. Although Japanese was the main focus in language training at first, the Army added several languages in the years following World War II. (U.S. Army photo)

Two firsts are associated with Greek. Its founder, Ann Arpajolu, was the first woman instructor at the school (arriving in September 1947), and she was also the first woman to become a language department head.

The biggest challenge facing the school was finding instructors to teach these languages. Thorpe solicited for men in uniform who were speakers of Arabic, Greek, Turkish, Persian or Korean – languages particularly difficult to staff. The school placed ads in foreign language newspapers in major U.S. cities where large ethnic communities existed.

The overall growth of languages at the Army Language School is as follows:

1947 – Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Spanish, Chinese, French, Greek, Korean, Portuguese and Russian

1948 – Albanian, Czech, Bulgarian, Danish, Swedish, Hungarian, Norwegian, Romanian, Polish, Serbian-Croatian, Lithuanian and Slovenian

1950s – Burmese, Indonesian, Malay, Thai, Vietnamese, German, Italian, Chinese-Cantonese, Finnish and Ukranian

By 1950, the Army Language School was teaching more than 20 languages. It was also in this year that the Cold War became “hot” in Asia as Soviet-backed North Korean troops unexpectedly stormed across the 38th Parallel into South Korea initiated the 1950-1953 Korean War.