By Cameron Binkley, Command Historian

When you think of resiliency, what comes to your mind? There are a thousand answers to that question. One of those answers can be summed up by a single word – Nisei. Nisei means “second generation” in Japanese and compares to Issei, or “first generation.” Traditionally, the term Nisei refers to a son or daughter of Japanese immigrants, who were born and educated in the United States and came of age during the World War II era.

Sam Sugimoto with Australian forces in New Guinea (Photo courtesy of the Command Historian office)

As immigrants, Japanese Americans had to overcome many obstacles to succeed in their new homeland – poverty, language barriers, racism. By emphasizing education, hard work, familial and communal ties, they were loyal to their adopted country but still respected their heritage. Japanese Americans provided for their families, pooled their resources to get ahead, met adversity bravely and thrived. One example of the adversity they faced involved the Immigration Act of 1924 which excluded Asians from U.S. citizenship. As a result, many Issei vested ownership of their businesses and farms in their children who had the legal protections of citizenship, or so they thought, until Pearl Harbor.

Still, many Nisei desired nothing more than to blend seamlessly into the American melting pot. However, Issei parents insisted their children continue to speak at least some Japanese even as the children lamented having to attend late afternoon Japanese classes. They resented drilling in Kanji while their non-Japanese classmates were free to play baseball. But some children even returned to Japan to study, becoming the vaunted Kibei – Nisei educated in both the U.S. and Japan. Regardless of where they learned Japanese, this second generation held a well of talent that became a strategic asset on that infamous day in December 1941.

As war loomed between Japan and the United States, the Army’s Military Intelligence Service, or MIS, established a school to train Japanese-speaking linguists, which is where the Defense Language Institute’s story begins. It did so by recruiting students from the many Nisei already drafted into the Army. Examples included Sam Sugimoto who served with the first units to reclaim captured American territory at Attu in 1943, or Thomas Sakamoto, who rose to the rank of colonel, interpreted for General Douglas MacArthur and later President Dwight Eisenhower.

The Army also recruited staff from draftees, including Kibei John Aiso, a Harvard trained lawyer that the Army first inducted as a private and assigned to a motor pool. Aiso could barely wait for his enlistment to end to return to practicing law when he met Lt. Col. John Weckerling, the school’s founder. Weckerling knew at once that Aiso was the perfect candidate to serve as the school’s first director. But Aiso refused, at first … until Weckerling told him his country needed him. Hearing so – for the first time in his life – Aiso changed his tune. He lead the school through WWII, becoming a full colonel, and later gained appointment as a California superior court justice.

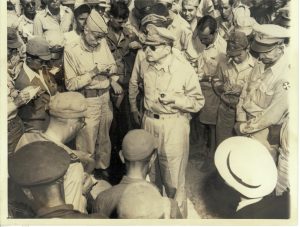

Thomas Sakamoto interpreting for Gen. Douglas MacArthur as he arrive in Japan. (Photo courtesy of the Command Historian office)

Other Nisei enlisted from the War Relocation Camps, established after all persons of Japanese ancestry were forcibly removed from the West Coast. Proving their loyalty against the bitterness of arbitrary detention, not one betrayed the United States. Fourteen MIS language school graduates served with General Frank Merrill behind enemy lines in Burma.

Thousands more deciphered captured documents, interrogated enemy prisoners, facilitated the surrender of Japanese forces across the Pacific Theater, or otherwise contributed “to shortening the war by two years,” according to General Charles Willoughby, MacArthur’s intelligence chief.

Of note as well, the Nisei established family traditions of military service that has benefited the nation until today. Sugimoto’s son John served in the 8th Radio Research Field Station, Phu Bai, Vietnam, while granddaughter, Spec. Emily Sugimoto, graduated from the Institute in 2014. Edwin Nakasone, who accompanied the language school from its wartime home in Minnesota to Monterey in 1946 and served in occupied Japan, also began a tradition. His son Paul is today the Commander of U.S. Cyber Command, and is the director of NSA.